(originally published in Business Insider)

When I called up my pregnant woman founder’s husband and said that I wanted to throw his wife a Zoom baby shower, he said, “Great!”

When I then said I wanted to surprise her during the baby shower with an unusual proposal to take time off from being a VC to help out at her startup so she could go on parental leave, he was more measured.

“I hope she says yes.”

Because, of course, there was zero historical evidence that this was not a terrible, horrible, no-good, very bad idea. Luckily, if anyone would be able to separate the wheat from the chaff, it was Emma, the pregnant founder I was offering to step in for.

Emma Sanchez Andrade Smith, founder of Jefa, is one hell of a badass woman boss, and I knew it even before she ever pitched me on the women’s consumer bank she started and named in honor of all badass women bosses. (“Jefa” means female boss in Spanish.)

Since my first check into Jefa from Brava by Magma Partners in early 2020, Emma had made swift progress, placing into the finals of TechCrunch’s 2020 Disrupt competition, raising money from the likes of Foundation Capital, DST Global, and Hustle Fund, and getting a waitlist of over 150,000 women clamoring for her verticalized challenger bank.

And she’d managed to do all this as a solo founder.

But therein lied the problem.

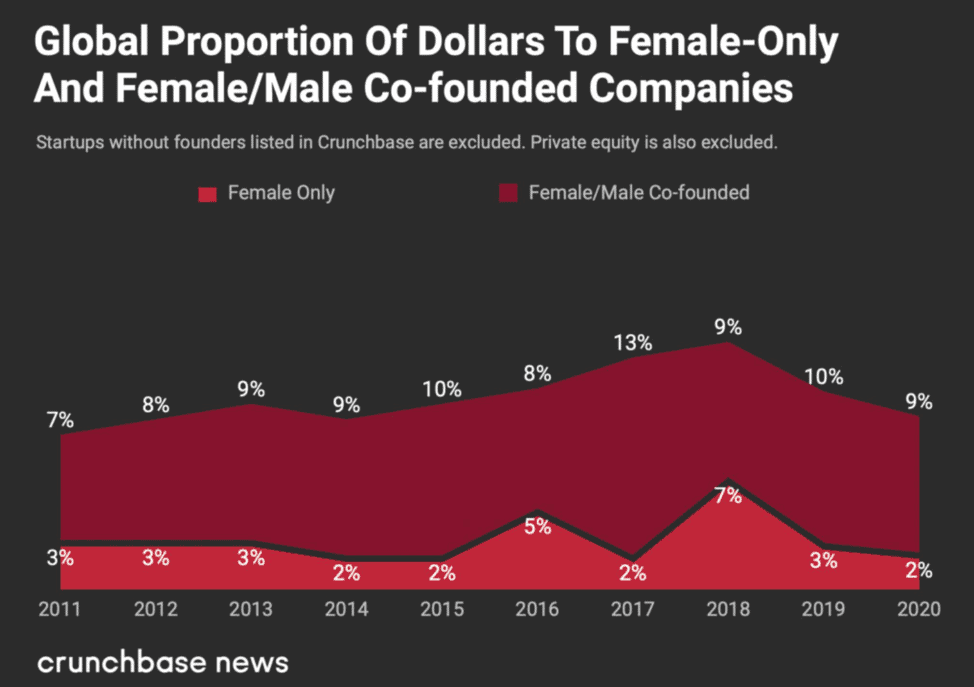

tl;dr: Solo women founders and all-women founding teams raised just 2% of all venture capital dollars in 2020, a record low. Womp womp.

As if it wasn’t clear enough that women founders have it bad when it comes to getting in front of and then getting funding from mostly male investing partners in the closed-door, network-driven business that is venture capital, enter 2020.

The year we spent locked at home while our children peed in the background of our Zoom calls (was that just me?) was also the year that featured a mass exodus of any and all potential VC funding to women founded startups. In short, 2020 was the year that the 90% white male investors of the venture capital industry shrank back into their existing networks and only funded the dudes they had once played beer pong with at Stanford.

And who were the founders who suffered most in this wasteland of capital for women founders? Any woman founder who didn’t have a male co-founder in the room.

Indeed, solo women founders and all-women founding teams raised just 2.3% of all VC dollars in the USA in 2020. This was down dramatically from the year before, and – amazingly – even less than what women founders had raised when we first started measuring these numbers more than a dozen years ago.[1]

And how much VC funding did pregnant women founders raise? Although no one wanted to look into those numbers since 2020 was already depressing enough, suffice it to say that anecdotal evidence indicates it was uh, really bad.

In a surprise to no one, pregnant women founders are not raising any money. Duh.

Not that there haven’t been a few pregnant women goddess bosses that have bucked the trend over the years. Audrey Gelman of The Wing had once been on the cover of Inc. Magazine as the first visibly pregnant founder to appear on the cover of a business magazine. Eric Schmidt, CEO of Fast Company and Inc. magazines reminded us of this historic moment in his video message for the Zoom baby shower we threw for Emma. One hundred other tech leaders also chimed in to encourage Emma that pregnancy didn’t have to be a PR crisis. Like Jen Rubio, the Founder of Away who was just named CEO while pregnant, Rachel Karrell, Founder of Koru Kids, and Sara Mauskopf, co-founder and CEO of Winnie, all who have raised millions while with child.

There were others. Toronto startup founder Joanna Griffiths had just raised $53 million for her ecommerce startup, refusing to let any investor who questioned her pregnancy into her round. And Kristen Anderson of Catch, who had recently gone viral with a tweet of her pregnant self that read, “I want every little girl — every child, really — out there to know this is what a venture-backed CEO negotiating for tens of million[s] of dollars looks like.”

Overwhelmingly, though, these examples were the rare exception, no thanks to investors, who categorically eschew pregnant founders.

As I had said to Anderson when trying to convince her to let me into her oversubscribed Series A, “I specialize in pregnant founders.” The truth was that it was really easy to specialize in pregnant founders. You just had to not discriminate against them. One way to do that was to not ask them weird questions about their uteruses (uteri?).

When I was pregnant with my twins, I was in Starbucks once when a dude told me it looked like I had three babies inside. “No, just two,” I responded, and got back to my muffin. Don’t get me started on the unsolicited belly stroking. The truth was, if random strangers on the street feel such unbridled confidence in acting like total Neanderthals when it comes to dealing with pregnant women, you can only imagine what kind of stuff a tone deaf or overtly discriminatory investor in a poorly regulated industry like startup fundraising can come up with when a full-bellied woman walks in to try and pry some cash money out of his clenched fist.

I’ve heard too many stories from women founders to share just one, but for a taste, see the recent anonymous story Backstage Capital Founder and Managing Partner Arlan Hamilton tweeted out. (Spoiler: These back-channel phone calls between investors about a female founder’s proposed family plans happen all the time.)

Not being overtly discriminatory with horrible questions was one way to specialized in funding pregnant founders. Another way was to actually write them checks. And a final, key way was to encourage pregnant women founders to take the parental leaves required to perpetuate the human race. Since the United States obviously sucked at this, I knew just who I needed to talk to for an expert opinion on how to do this better. A freaking Scandinavian.

Enter Sophia Bendz. An early Spotify employee turned acclaimed seed investor, Bendz was a partner at Cherry Ventures and was the VC friend in my angel group, The Angel Collective, that I had bamboozled into writing a book with me about women founders and founders. With five small children between the two of us and more than a year into a global-pandemic-infused-childcare-crisis, we were behind.

When I asked Sophia why Nordic countries gave women founders parental leaves when other countries like the USA did absolutely nothing, Bendz explained: “In Sweden both parents are valued as equally important for the secure attachment and the development of the child. That’s why we’re entitled to 1.5 years of parental leave per family. Once the child is ready we have high quality childcare centers that are subsidized by the government in order to create a sustainable situation for families — and especially for women — to come back into the work force.”

I paraphrased, “So you mean Sweden actually values mothers?”

Why I Decided to Step in, and How my Working Mother Rage Fueled this Decision

But back to my bad idea.

During the 20-month time period from December of 2019 until September of 2021, my three kids will have had in-person school for a grand total of one month in Argentina, where I live on a Southern Hemisphere school schedule and where Covid has never been worse. (As of June 2021, we are back in lockdown, with few vaccines on the horizon.) Working a demanding job as an investor from home with three small children had made this the most challenging time of my life when it came to my career, and I say that after having actually worked part-time from the hospital while my newborn twins spent two months in the NICU when they were born two and a half months early.

The pandemic had unequivocally ignited my working mother rage. And I was one of the extraordinarily privileged ones. I had financial stability, childcare, fast internet for Zoom school, a nice, safe home, and a partner who shared equally in caregiving. And yet I was still so sick of pretending all of this wasn’t so hard. (Cue Gloria Steinem’s quote: “The truth will set you free. But first it will piss you off.”)

That’s why when Emma told me she was pregnant, I felt an indescribable visceral feeling of anger emerge from my body as I imagined what this might mean for both her startup’s fundraise and for her first few months as a mother.

Not today, Satan.

How this Will Work, or How I Will Not Ruin My Founder’s Startup

The main thing I told Emma after the Zoom baby shower, when I called her to discuss what the hell I had just done in front of her confused friends and family was:

“This is entirely up to you. If you want to accept this I want it to be on your terms. I also don’t want to mess up Jefa.”

My husband, astutely, had said that this could be interpreted as the most stealth hostile startup takeover ever. Despite the close relationship I had built with Emma that I hope allayed any fears of some kind of crazy Machiavellian machinations on my part, I also addressed that head on, telling her point blank that I had no delusions of being a great fintech operator, nor did I have any intention of sticking around long-term as anything but her investor. Me stepping in for a few months as an operator was a one-time offer for Jefa, and a one-time thing in my own career as an investor. (I love investing, and have no plans of making a habit of stepping in for founders every time they get knocked up.)

Once Emma said an enthusiastic yes to the general idea, I then sought clarity about what my role should actually be. Again — her company, her choice. When I had initially toyed with the idea of suggesting this to Emma at all I had sought feedback from the VC firm, Magma Partners, where I am a partner, and from my angel group of other women VCs. I remembered Lolita Taub and Maren Bannon initially asking what kind of role I would suggest to Emma. Acting CEO? It didn’t take a genius realize that was patently a bad idea.

Instead, all signs pointed towards Jefa’s CFO, Malavika Chugh. She had been there since the beginning, ever since she applied to be my MBA intern at my VC fund while she was studying at Kellogg. (She was overqualified for the internship, but she hit it off with Emma.) She was undoubtedly the person best qualified to step in as acting CEO to the team of 15. As for me, I would be relegated to specific projects I could ideally not mess up, and which, as I told Emma, I hoped would “not be very hard.”

Why No VCs Have Done this Before, Should More VCs Do This in the Future, What Is the Overall Message to the Industry

It is a well-established best practice for early-stage, high-growth startups to do things that are not scalable in efforts to create a flywheel that will one day achieve escape velocity.

When I had just started at Twitter in 2009, for example, one day a user knocked on the front door of the office. The colleague next to me, who had an MBA but was acting as a temporary receptionist, answered the door and helped the user to personally upload a bathing suit shot to her user profile. This was not a sustainable solution to user support. But it did emphasize to both the user and the company of then 50-ish teammates that Twitter was a place that cared about users, no matter how big it got.

Powerful change happens in the same way.

Immediately after I offered to step in to help Emma during her Zoom baby shower, the recently hired head of marketing at Jefa, Isabel Espinoza, sent a message to the rest of the team saying how meaningful it was for her to see this happen given her own horrible experience with maternity leave:

“I want to share a personal experience: When I worked for a governmental institution and my maternity leave ended, I had no special considerations whatsoever neither by my colleagues nor by the institution. I had to pump milk at the bathroom or hide myself behind banners if the bathrooms were dirty. My colleagues were disgusted [by] my breast milk and [I] received zero support from them. Men were vocal on how inconvenient my lactation was and women either were ashamed or ignored the situation. Eventually this ended my breastfeeding experience. I am sharing this so I can tell you that what we just witnessed on Emma’s baby shower is SO SPECIAL AND INSPIRING! Listening to all those powerful people support Emma’s pregnancy and be happy about it blew my mind. Before Jefa, I honestly lost my faith in change, diversity, and working environments. But the past couple of weeks had given me back the stamina and the urge to make the world a better place.”

In the industry at large, other women founders and women VCs shared all kinds of awful stories about what had happened to them when they were expecting or on parental leave. Along the way, many people also flattered me personally, like Federico Antoni, Partner at ALLVP, who tweeted, “There are indeed VCs that add value… and there’s also @Claire.” (To be clear, I will 1000% be printing this on a towel to throw at my children every time I disappoint them.)

The point was that it was a visible, high-touch, and hopefully effective action alongside a ton of other actions that other women founders and women VCs like Francesca Warner at Diversity VC and Sarah Kathleen Peck at Startup Parent and Sara Mauskopf at Winnie and Charlotte Michailidis at Parenthood Ventures and Jenny Lefcourt at All Raise were taking part in to start the flywheel that could one day achieve escape velocity to ultimately eliminate the discrimination facing pregnant women founders.

It wasn’t like we didn’t know exactly what had to be done, after all. We just had to get people to actually do it.

Stop asking pregnant women illegal questions. Start writing checks. Give women founders parental leave. The end.

tl;dr: women founders so pregnant, Silicon Valley so lame.

[1] https://news.crunchbase.com/news/global-vc-funding-to-female-founders/

tl;dr pregnant women founders so awesome, Silicon Valley so lame!